There’s a getting-to-know-you game called “Two Truths and a Lie” that I have played many times. You tell three outrageous things about yourself, but only two are true. With all the crazy things that have happened in my life, it’s not hard to baffle the people I’m playing with. I always say “I spent 3 weeks on life support,” and people are surprised when I say that I’m not kidding.

There’s a getting-to-know-you game called “Two Truths and a Lie” that I have played many times. You tell three outrageous things about yourself, but only two are true. With all the crazy things that have happened in my life, it’s not hard to baffle the people I’m playing with. I always say “I spent 3 weeks on life support,” and people are surprised when I say that I’m not kidding.

It’s been 11 years since I survived a condition so severe that doctors had given up hope for me, and encouraged my family to “make arrangements”. And in light of my recent health struggles, I felt that it was important to document my memories of how I cheated death. And since I’m a blogger, I share my story with you here.

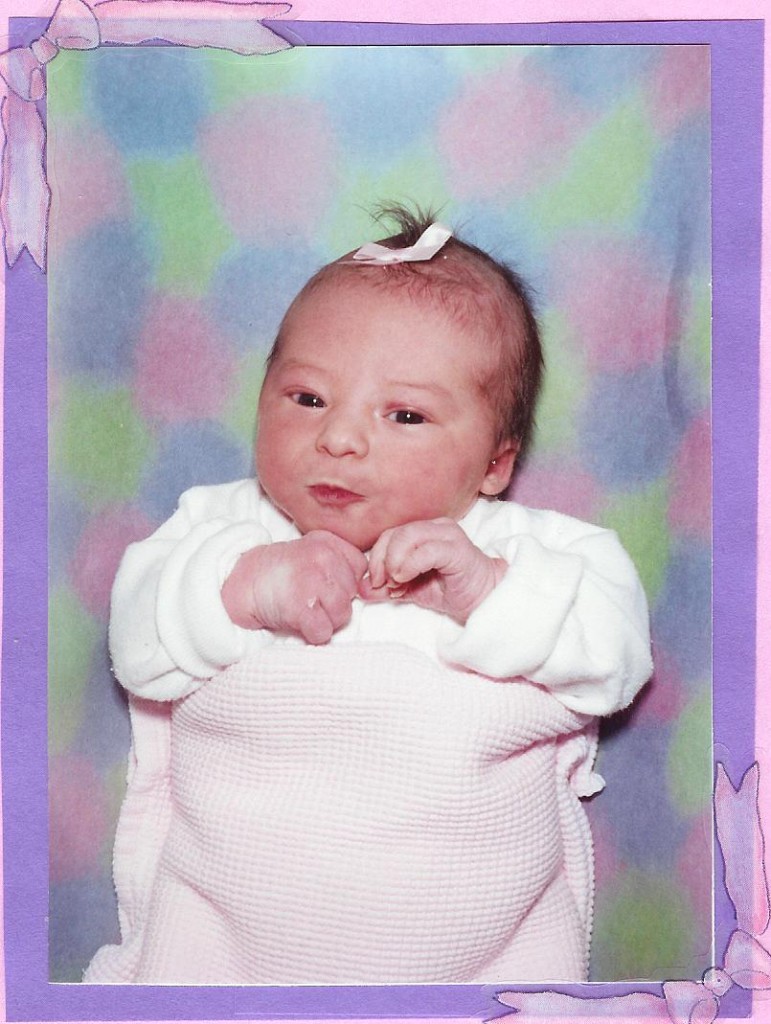

How did I get such a bizarre and life-threatening illness? It was a combination of things, but I was recovering from post-partum trauma, blood loss and sepsis. And because it happened in the days following Rosie’s birth, I might as well tell her birth story too. In fact, there’s really no way to separate the two events.

In fact, there’s really no way to separate the two events.

I found out that I was pregnant in January of 2000. I had only been married 9 months, and felt incredibly unprepared to be a mother. I dealt with chronic nausea and vomiting through 8 months of my pregnancy, and lost 30 pounds in my first trimester. Many people commented that it was strange for me to have such a difficult time keeping food down, but I eventually got back to my pre-pregnancy weight when I was ready to deliver. I could barely stand my excitement to see my little Rosie.

I was induced for labor at 41 weeks. The delivery was pretty routine and Rosie was born healthy and strong. Unfortunately, the placenta would not deliver. It was attached tightly to my uterine wall, and it finally came out after 45 minutes of my OB/GYN tugging at the placenta while I was hemorrhaging. A blood transfusion was considered, but they didn’t have enough AB+ on hand in the blood bank.

So first factor – trauma of delivery and significant blood loss.

I was exhausted leaving the hospital when I left two days later. But that didn’t stop me from shopping at Babies R Us, going to my cousin’s baby shower, and driving around to show of my gorgeous new infant. I considered going to church with a 3-day-old in tow, but stayed home to rest at the encouragement of my husband. I nursed and napped, and woke up feeling not quite right. Within two hours I had spiked a high fever and was trembling with chills. I knew this wasn’t a good sign, so I headed to the Emergency Room.

I was exhausted leaving the hospital when I left two days later. But that didn’t stop me from shopping at Babies R Us, going to my cousin’s baby shower, and driving around to show of my gorgeous new infant. I considered going to church with a 3-day-old in tow, but stayed home to rest at the encouragement of my husband. I nursed and napped, and woke up feeling not quite right. Within two hours I had spiked a high fever and was trembling with chills. I knew this wasn’t a good sign, so I headed to the Emergency Room.

I remember being dropped off in front of the Cottonwood Hospital ER, only about 50 feet from the entrance. But I was so weak that a nurse caught me falling halfway in, grabbed a wheelchair, and wheeled me straight into a treatment room. After a battery of tests, I was diagnosed with a severe kidney infection. I had been hospitalized 17 months prior with a kidney infection, and spent 5 days inpatient at the same hospital. The blood and urine was cultured out, and the raging infection was caused by E. coli.

I was admitted, and pumped full of IV antibiotics. I remember on my prior hospitalization, they gave me Rocephin, and it didn’t work well, so they gave me another antibiotic. When they put me on Rocephin again, I mentioned that it hadn’t worked in the past. But they assured me that this drug was the standard of care, and 24 hours of treatment would be enough to go home on oral antibiotics. I felt yucky, but was happy I could still have my baby stay with me in the hospital. My grandparents were leaving on a mission that week, and the extended family was having a farewell dinner Monday evening. I really wanted to go, and the doctor was more than happy to release me in time to go to the party.

Second factor – sepsis.

I enjoyed the time with my family, showed off Rosie and tried to act as positive and energetic as I could. But I was exhausted. I didn’t feel like staying very long, and I asked my mom to come home with me to help out with Rosie overnight. I was really weak, and felt more short of breath the later it got in the evening. I was diagnosed with asthma at age 12, so I had a few inhalers laying around. I took a few puffs, tried to relax, but I just didn’t feel right. I was stubborn enough to hold off on going to the ER again until 4 am, when my fingers, toes and lips were turning blue.

I enjoyed the time with my family, showed off Rosie and tried to act as positive and energetic as I could. But I was exhausted. I didn’t feel like staying very long, and I asked my mom to come home with me to help out with Rosie overnight. I was really weak, and felt more short of breath the later it got in the evening. I was diagnosed with asthma at age 12, so I had a few inhalers laying around. I took a few puffs, tried to relax, but I just didn’t feel right. I was stubborn enough to hold off on going to the ER again until 4 am, when my fingers, toes and lips were turning blue.

The next few hours are kind of blurry. In triage, they checked my oxygen saturation level, which was at a critically low 70%. I remember being swarmed by doctors, medical students, and nurses. I started with oxygen on a nasal cannula, but they soon put a face mask on me. I started feeling a little bit better after the oxygen and some IV fluids, and the hysteria around my hospital bed calmed a bit. Steve (my ex-husband) and my mom were talking about how hungry they were, and how it was probably going to be a couple of hours before anything important happened. My mom left to get breakfast at McDonald’s across the hospital parking lot.

In the minutes while my mom was gone, I went into shock and my vitals took a nosedive. Medical jargon was being yelled out and it was evident they were planning to transfer me to the ICU. They told me that the oxygen mask wasn’t giving me enough help, and they were going to put a tube down my throat to help me breathe. My mom got back from McDonald’s, and couldn’t believe that my status had worsened so quickly. The last thing I remembered was Steve complaining to my mom that she forgot to get salsa for his breakfast burrito (terribly immature, I know, but he was in shock too).

I was transfered to the Intensive Care Unit, intubated, and sedated into a medically-induced coma. From this point, the recollections in the ICU are from my family. After chest x-rays, lab work, and a bronchoscopy with lung biopsy, I was diagnosed with diffuse alveolar damage leading to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, also known as Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome, or ARDS.

According to National Institutes of Health,

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening lung condition that prevents enough oxygen from getting into the blood. ARDS can be caused by any major swelling (inflammation) or injury to the lung. Some common causes include:

- Breathing vomit into the lungs (aspiration)

- Inhaling chemicals

- Pneumonia

- Trauma

- Septic Shock

ARDS leads to a buildup of fluid in the air sacs. This fluid prevents enough oxygen from passing into the bloodstream. The fluid buildup also makes the lungs heavy and stiff, and decreases the lungs’ ability to expand. The level of oxygen in the blood can stay dangerously low, even if the person receives oxygen from a breathing machine (mechanical ventilator) through a breathing tube (endotracheal tube). ARDS often occurs along with the failure of other organ systems, such as the liver or the kidneys.

Typically people with ARDS need to be in an intensive care unit (ICU). The goal of treatment is to provide breathing support and treat the underlying cause of ARDS. This may involve medications to treat infections, reduce inflammation, and remove fluid from the lungs. A breathing machine is used to deliver high doses of oxygen and a continuous level of pressure called PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) to the damaged lungs. Patients often need to be deeply sedated with medications when using this equipment.

About a third of people with ARDS die from the disease. Survivors usually get back normal lung function, but many people have permanent, usually mild, lung damage. Many people who survive ARDS have memory loss or other problems with thinking after they recover. This is due to brain damage that occurred when the lungs weren’t working properly and the brain wasn’t getting enough oxygen.

(More about ARDS and Sepsis)

At this point, the doctors prepared my body for sedation, mechanical ventilation, broad spectrum antibiotics, catheters, feeding tubes, and everything else needed for a living on life support for long enough for my body to heal. I was very fortunate to not receive a tracheotomy. The doctors told my family to plan on an extended stay in the ICU. But after a few days, I wasn’t doing much better. Dips in my vital signs were so significant that social workers began to talk to my family members about “making arrangements” in the event that my situation worsened to death. But at this point, my family was offered the chance to have me enrolled in a ventilator research protocol, sponsored by the NIH, called ALVEOLI. This is when the tides began to turn in my recovery.

Most people who experience ARDS are over 60 years old and usually fall into multiple-organ failure. But because I went into the illness otherwise healthy, I returned from a critical state more quickly than most patients with ARDS. There was only one day that I was on the vent where I wasn’t sedated. It was the most hellish day that I’d ever experienced. Because the tube was still down my throat, my ability to communicate verbally was taken away. My muscles had atrophied so much over the weeks of sedation that I was too weak to hold a pencil to write anything. I remember lots of painful suction from the tube. But the worst part of it all was the ICU psychosis.

ARDS patients are at great risk for multiple organ dysfunction, and the brain is usually the most affected organ. According to the ARDS Foundation,

“Health care professionals are becoming increasingly concerned not only with survival, but also with the quality of patients’ lives, which is determined in large measure by their neuropsychological outcomes. At 6 months following ALI/ARDS, the proportion of patients complaining of psychiatric, cognitive, and neurologic symptoms were 57%, 32%, and 44%, respectively. In our own studies and those of others recently, it has been determined that up to 80% of patients experience acute delirium in the ICU during their bout of ALI/ARDS. We have shown that delirium in the ICU is associated with a 9 times higher likelihood of cognitive impairment at the time of hospital discharge. Lastly, 33% to 80% of survivors of ALI/ARDS have long-term cognitive impairment when studied with comprehensive tests. This sort of ongoing brain dysfunction can be akin to an acquired dementia of sorts.”

With how much I DON’T remember about the hospital stay, it’s interesting how vivid my recollections of my ICU psychosis are, even a decade later. Despite what the doctors told me, I was certain that I got sick because I actually gave birth to twins. Rosie was born, and the placenta wouldn’t deliver because it was supporting another baby. I thought my body short-circuited because it had wait 5 days to give birth to the other baby. I thought that the crown molding at the top of the ICU room was a specialty baguette that helped premature infants “ripen,” like a cutting-edge incubator. I also thought I was in a high-rise hospital building in “urban Salt Lake,” and I wanted to go home by subway because there was excess construction around the hospital.

When it was time for me to have another CT scan to check on my chest and abdomen, I looked up at the styrofoam ceiling in radiology and saw messages poked with a pen into the ceiling saying that “having a CT scan will be the most traumatic experience ever” and I should “request a less invasive radiological procedure.” I thought that the tachycardia I was experiencing was due to a high-sodium feeding tube diet, and once I could speak, I would like to be assured that I would not be given a diet with excess sodium (and I persisted until my ICU nurse wrote a message on the white board in my room to remind the other nurses.

Through the time that I was in the hospital, I worked with physical therapists 2-4 times a day. I was told that as soon as I could walk around the entire unit unassisted, I could go home. At first, all they could do was exercise my fingers for me until I was strong enough to grasp a pencil. Then they had me work with Therabands to strengthen my other arm muscles. We worked on techniques to move me around in the hospital bed. Leg PT went from wiggling toes, to flexing my foot and bending my knees. The first time I stood on my two feet after 3 weeks in a hospital bed, I lasted about half a second before I flopped back on the bed. But then I got strong enough to march in place. Then I worked on getting out of the bed to use the commode (as I was completely mortified by using the bedpan).

Life got a lot better once I had been extubated. I was able to recover from the inflammation in my throat caused by the ventilator. I was able to find ways to communicate as my body strengthened and my voice came back. The effects of the amnesiac medication, Ativan, wore off and I started to feel like I was more in my right mind. I was motivated to see my baby, and strictly complied with all physical therapies in order to gain strength to leave the ICU. I was initially transferred from the ICU to a shared room. I remember the first time I saw Rosie after all these painful weeks. I had nurses prop pillows all around me, and my beautiful daughter was laid in my weak, atrophied arms. My voice was still scratchy and weak from the ventilator tube, but I still attempted to sing lullabies to her. All of the baby stuff for Rosie took up most of the space in the shared room, and I was told that they were working on a private room.

As soon as it was available, I was transferred to the “VIP suite” on the surgical floor (where any celebrity, or general authority’s wives, recover after surgery.) It had a gorgeous mountain view and was spacious (meaning monumentally far from the bathroom once I was strong enough to not use the bedside commode). I spent the following days watching the Sydney 2000 Summer Olympics from my hotel room, along with a bunch of TV shows that my dad recorded for me to stay sane. I spent a lot of time resting between aggressive physical therapy visits. I had Rosie brought into me at the hospital as often as my strength allowed, and did the pillow-prop technique until my arm muscles were strong enough to hold her unassisted. I remember yelping with joy the first time I walked across my hospital room, supported by my gigantic IV pole, to use the restroom by myself. I could have my urinary catheter removed, and was excited to not be stuck with the bedpan. At that point I could have real baths instead of sponge baths in bed.. Next I started walking around the floor of the unit, then faced my nemesis – THE STAIRS. It was truly one step at a time.

After a week on the Med-Surg floor, doctors were finally discussing my release from the hospital. There was some debate as to whether I should be released to a rehab hospital, or if I could stay at my parents’ house. Ultimately, it was decided that I’d transition back into real life easier if I was at home. For the ICU stay, I was given an NG tube for nutrition, and my meals came from an IV pole through my nose. A few days after I was moved out of the ICU, the “nose food” was discontinued and I started eating very small meals. It was very difficult to eat because my throat and vocal cords were extremely swollen from the ventilator. I had to chew each bite very thoroughly, and would choke often. It was hard to get all my nutrients, so I had to drink Boost or Ensure supplement drinks to get by.

Once I was released, I was pushed out to my car in a wheelchair. It was the first time I’d been in the sun in weeks, and it was a beautiful October day. We went straight to my parents’ house and I flopped into a cushy pink La-Z-Boy (which would be my favorite spot for the 6 months I lived there.)

Within a few hours, I started having a strange pain in my left arm, particularly intense around the area my PICC line was removed earlier in the day. I thought it was normal, since I’d had the line in for several weeks. But the next day it started to swell and turn red, and felt very hot to the touch. I had my home health nurse look at it, and she got in touch with my doctor. I was instructed to go to radiology at Alta View hospital immediately for an upper extremity ultrasound. Having just been pregnant, I had several completely normal ultrasounds where the radiology tech casually talked through the procedure. But this tech had this worried intensity in his eyes. He excused himself from the room and called my doctor, who then wanted to talk to me. The ultrasound uncovered a massive blood clot from my middle fingertip to my armpit. The clot most likely began forming 2 days prior, while still in the hospital, when shots of heparin were discontinued.

In most cases, a clot of this size would mean immediate hospitalization. But since I’d been released the day before from a month-long hospital stay, my doctor had it set up for me to have anticoagulation therapy from home. I would get a week of twice-daily shots in the gut of Lovenox, a strong blood thinner. Unfortunately, my “postpartum flow” was not taken into consideration. Because I’d been bedridden for so long, my body hadn’t had the chance to shed all of the fluids and tissues from my uterus after delivery. I was already weak, anemic, and had ridiculously low levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit. I felt like I was hemorrhaging, and it warranted another trip to the ER. After an ultrasound on my belly, and another ultrasound on my arm, I was told to stop the shots of Lovenox because my blood had been thinned too much.

I was instead put on Coumadin, an oral blood-thinner than requires frequent blood testing. Many people joke that it has the same affect on your body as rat poison. It affects so many elements of your life – you have to avoid certain foods, you are more prone to bruising, your blood can get too thin or not thin enough, and you can’t be on hormonal birth control. It can cause fatigue, fainting, flu-like symptoms, gastrointestinal issues, and many other unpleasant side effects. So it’s hard to separate the recovery from ARDS to the setbacks caused from anti-coagulation therapy. And because I’d been on such strong antibiotics for so many weeks, I had candida yeast growth issues ALL OVER my body, not just the usual places. Sparing all the disgusting details, I will say that it’s very possible and uncomfortable to have yeast issues under your fingernails, and between your fingers and toes.

But when I got discouraged with my recovery, I had to put it into perspective. I was alive. I survived despite sketchy odds. I had an amazing support network. And slowly, my health and my strength improved. By Christmas time, I was strong enough to go out in public, and one of my biggest victories was holding Rosie as I walked up a flight of stairs so we could get a picture with Santa for her first Christmas.

So that is my ARDS story. That is the background on why I’m so prone to respiratory problems and other health struggles. This is a reason I have postponed having additional children. That is why it is difficult for me to exercise and lose weight. That is why I still struggle with violent flashbacks of my ICU psychosis. I beat the odds. I am a survivor.